The Vietnam War was one of the most turbulent chapters in American foreign policy, defined by gradual entanglement, mounting costs, and a contested withdrawal. The escalation of U.S. involvement from advisory support in the 1950s to full-scale military engagement in the 1960s did not occur through a single decision but through a series of incremental commitments shaped by Cold War anxieties, political calculations, and flawed assumptions. By the time the policy of Vietnamization was enacted under President Richard Nixon in 1969, the United States had become deeply embedded in a war it could neither decisively win nor politically sustain. The path to Vietnamization reveals the interplay between ideology, misjudgment, and the limits of American power.

The Origins of Involvement

The roots of U.S. involvement in Vietnam lie in the broader strategy of Cold War containment. Following the defeat of French colonial forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the Geneva Accords divided Vietnam into the communist North and the so-called democratic South. The United States, committed to halting the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, supported the establishment of the Republic of Vietnam under Ngo Dinh Diem. American aid, advisors, and diplomatic backing quickly flowed into the region.¹

Diem’s regime, however, was authoritarian and unpopular, relying heavily on American support to suppress dissent and maintain control. The Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations framed this alliance as necessary to prevent a “domino effect” in Asia, where the fall of South Vietnam would allegedly trigger a cascade of communist victories across the region, resulting in a communist stronghold in the East that America could never topple.² As a result, what began as limited support evolved into a moral and geopolitical obligation. By the early 1960s, the U.S. had committed over 15,000 military advisors. The groundwork for escalation was firmly in place.

The Turning Point: Johnson and the Logic of Escalation

President Lyndon B. Johnson inherited a deteriorating situation upon taking office in 1963, following John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Diem had been assassinated with tacit U.S. approval, and South Vietnam’s political instability deepened. In August of 1964, the Gulf of Tonkin incident, in which U.S. ships were allegedly attacked by North Vietnamese forces, provided Johnson with justification to seek congressional approval for broader military action. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution granted him expansive authority to conduct military operations without a formal declaration of war.³

This moment marked a critical shift. Under President Johnson, the U.S. launched Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965, a sustained bombing campaign against North Vietnam, and began deploying combat troops en masse. By the end of 1965, over 180,000 American soldiers were in Vietnam.⁴ Despite assurances that victory was near, the war quickly devolved into a brutal and protracted conflict. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong, utilizing guerrilla tactics and extensive knowledge of the terrain, proved far more resilient than American planners anticipated.

Attrition and the Limits of Power

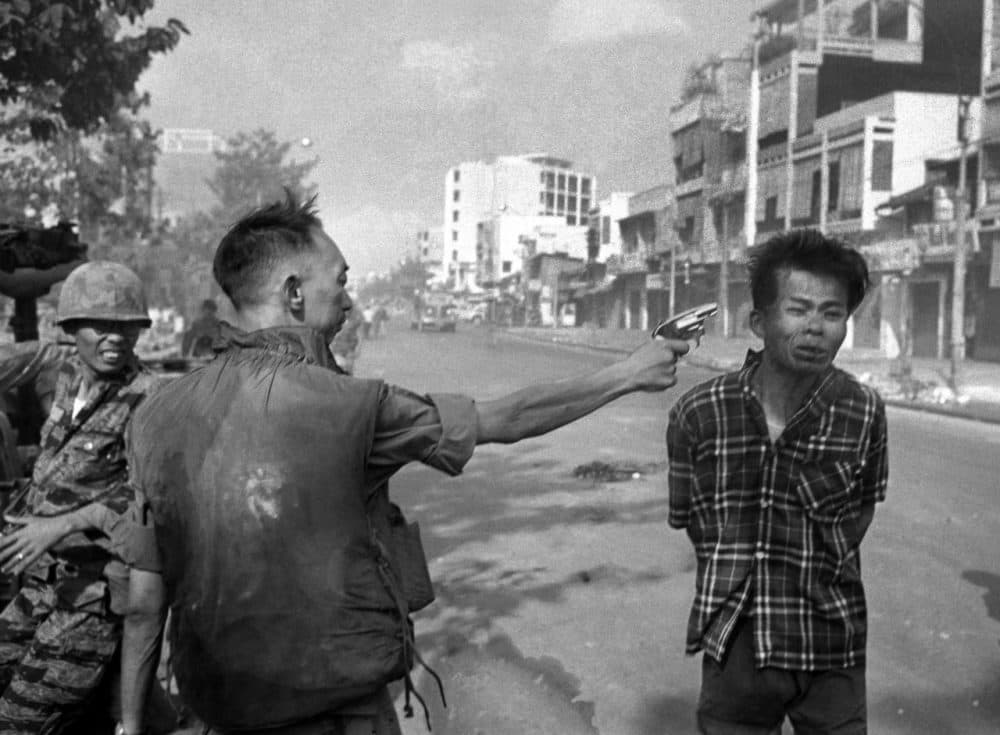

The strategy of attrition, aimed at wearing down enemy forces through superior firepower, failed to produce clear results. Body counts replaced territorial gains as a measure of success, and public skepticism began to mount. The Tet Offensive in January of 1968, a massive and coordinated assault by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces, struck key urban centers across South Vietnam, including the U.S. embassy in Saigon. Though a tactical failure for the communists, Tet shattered the perception that the U.S. was winning the war.⁵

Televised images of combat, growing casualties, and reports of atrocities like the My Lai Massacre further eroded domestic support. Journalists and returning soldiers increasingly challenged the official narrative, contributing to what scholars termed the “credibility gap” between government statements and the reality on the ground.⁶ Public protests swelled, and President Johnson, recognizing the political toll, announced in March of 1968 that he would neither seek re-election or accept his party’s nomination.

Nixon and Vietnamization: Shifting the Burden

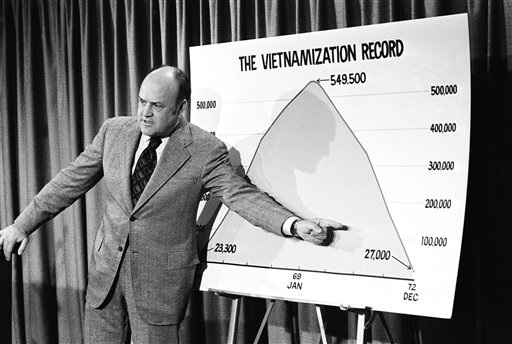

When Richard Nixon assumed the presidency in 1969, he faced a nation weary of war but wary of defeat. His administration introduced Vietnamization, a policy aimed at gradually reducing American troop levels while increasing the South Vietnamese military capacity (ARVN). The goal was to transfer responsibility for the war to the South Vietnamese, allowing for a so-called “peace with honor” withdrawal of U.S. forces.⁷

Vietnamization was not an immediate retreat but a strategic recalibration. U.S. troop numbers began to decline, from a peak of 543,000 in 1969 to around 69,000 by 1972, but the war itself expanded into neighboring countries like Cambodia and Laos in an effort to disrupt North Vietnamese supply lines.⁸ These incursions sparked further domestic outrage, culminating in tragic events such as the Kent State shootings in May of 1970.

Despite ongoing peace talks in Paris, it became increasingly clear that the South Vietnamese government lacked the legitimacy and capability to survive without American support. Nonetheless, Nixon pressed ahead with disengagement, culminating in the Paris Peace Accords of January of 1973. American forces withdrew, though official fighting between North and South Vietnam continued until the fall of Saigon in 1975.

The Legacy of Escalation

The escalation of the Vietnam War revealed the perils of incremental commitment without clear objectives or public consensus. Each administration, unwilling to appear weak, deepened American involvement in the hopes of avoiding defeat, only to entrench the country further in an unwinnable conflict. The pivot to Vietnamization acknowledged these limits, but did not erase the war’s human, political, and moral costs.

Long-term consequences included a profound shift in American foreign policy thinking. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 sought to reassert congressional authority over military engagements.⁹ Public trust in government, already shaken by the war, was further eroded by related scandals like Watergate and economic instability caused by “stagflation”. The so-called “Vietnam Syndrome”, a reluctance to engage in foreign interventions, shaped U.S. strategy for decades.

In the end, the path from escalation to Vietnamization underscores a central lesson of modern American history. Military power cannot substitute for political legitimacy, and public support is not an afterthought. It is a requirement. The Vietnam War became not just a battlefield conflict, but a national reckoning with the limits of American influence and the costs of hubris.

Bibliography

- Logevall, Fredrik. Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam. University of California Press, 1999.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. Strategies of Containment. Oxford University Press, 1982.

- U.S. Congress. Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, August 1964.

- McNamara, Robert S. In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. Vintage Books, 1995.

- Hallin, Daniel. The “Uncensored War”: The Media and Vietnam. Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Appy, Christian G. Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam. University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Nixon, Richard. “Vietnamization.” Speech to the Nation, November 3, 1969.

- Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. Viking, 1983.

- U.S. Congress. War Powers Resolution, 1973.

Leave a comment