Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, marked a decisive turning point in the relationship between science, public consciousness, and political reform in the United States. More than an exposé of pesticide use, the book fundamentally altered how Americans understood their environment and their responsibility to protect it. Carson reframed environmental decay in the minds of the public. Initially viewed as an abstract and inevitable consequence of technological progress, Silent Spring argued that environmental destruction was a direct result of human decision-making, corporate power, and governmental neglect. In doing so, Silent Spring catalyzed the modern environmental movement by transforming ecological concern into a moral and political imperative.

Science, Authority, and Public Trust

Before Silent Spring, environmental issues rarely occupied the center of national political discourse. Chemical pesticides, such as DDT, were widely celebrated as symbols of postwar progress, credited with boosting agricultural productivity and controlling disease. Government agencies and chemical manufacturers reassured the public that such substances were safe, effective, and essential to economic growth. This trust in scientific authority, however, was unchallenged. The so-called data collected by such institutions flowed to citizens without meaningful public scrutiny.

Carson disrupted this dynamic by challenging the assumption that scientific advancement was inherently benign. Drawing on years of biological research, she exposed the ecological consequences of indiscriminate pesticide use, demonstrating how chemicals accumulated in food chains, poisoned wildlife, and posed long-term risks to human health.¹ Importantly, Carson, as one of the foremost scientific communicators of her time, translated complex scientific data into accessible prose, empowering ordinary citizens to question expert claims and demand accountability. In doing so, she repositioned science as a tool for public inquiry rather than an instrument of institutional reassurance.

The Assault on Credibility by the American Government and Chemical Manufacturers

The reaction to Silent Spring revealed deep anxieties about authority and dissent in Cold War America. Chemical companies and their allies launched aggressive campaigns to discredit Carson, framing her as alarmist, emotional, and unqualified.² These attacks often relied on gendered assumptions, portraying Carson’s concerns as hysterical rather than scientific. Such criticism, however, backfired. Rather than silencing Carson, it underscored her central argument, being that powerful interests were willing to dismiss evidence to preserve profit and control.

CBS’s broadcast of Carson’s interview showed that she was a calm and reasonable scientist, starkly contrasting the perception that pesticide manufacturers had been pushing. Public defense of Carson by scientists, journalists, and civic organizations elevated the book beyond a scientific critique into a broader cultural challenge. The controversy itself became a vehicle for mobilization. Americans began to see environmental harm not as accidental, but as the predictable outcome of unchecked industrial power operating with minimal oversight.

From Awareness to Activism

Silent Spring succeeded, because it connected ecological damage to everyday experiences. Carson warned that the loss of birds, insects, and clean water would not remain distant or theoretical. It would eventually affect homes, food, and future generations.³ This framing helped shift environmentalism from a niche conservation ethic to a mass movement concerned with public health and institutional accountability.

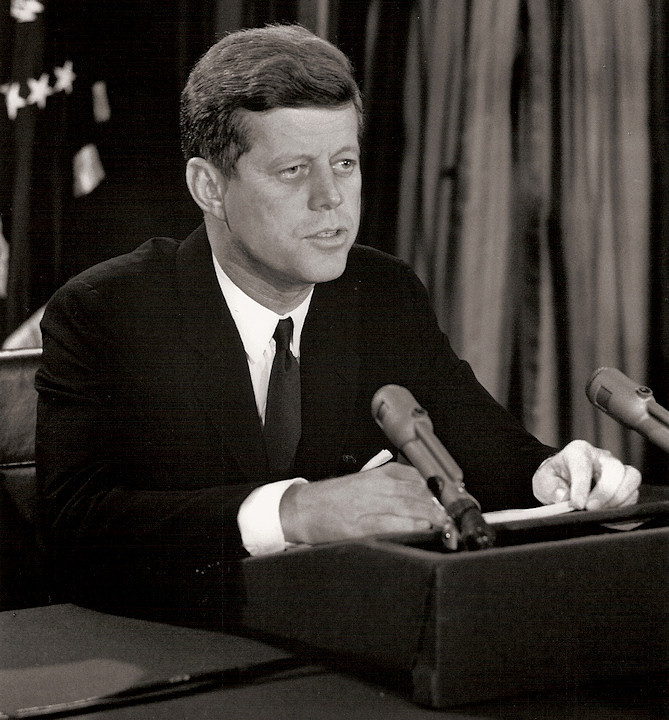

The book’s influence was quickly felt in the political arena. President John F. Kennedy ordered a federal review of pesticide policies, and congressional hearings soon followed.⁴ While Carson herself avoided overt political advocacy, her work laid the intellectual foundation for regulatory reform. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, environmental protection had become a legitimate policy objective rather than a peripheral concern.

The Legacy of Silent Spring on Policy

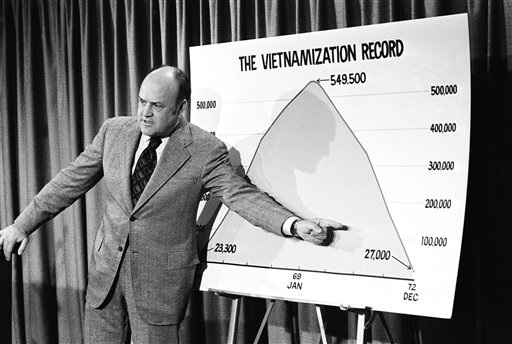

The long-term effects of Silent Spring were profound. The establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and the eventual ban of DDT in the United States reflected a new willingness to regulate industry in the name of ecological and public health.⁵ These reforms were not inevitable. They emerged from a cultural shift that Carson helped initiate by changing the perception of environmental harm from a collective moral failure to an unfortunate side effect of progress.

Equally important was the movement’s emphasis on citizen engagement. Environmental activism increasingly relied on grassroots organizing, public education, and litigation, echoing Carson’s insistence that informed citizens must hold institutions accountable. Her work demonstrated that environmental protection was inseparable from democratic participation.

A New Moral Framework

In my final analysis, Silent Spring reshaped the environmental movement by redefining the relationship between science, power, and the public. Carson achieved two aspects. She warned of ecological collapse, and she challenged Americans to reconsider the costs of unquestioned technological optimism. Her legacy lies in the enduring idea that environmental stewardship is a civic responsibility.

In the early 1960s, a time when public faith in institutions was high and dissent was often marginalized, Carson gave voice to a new form of public skepticism grounded in evidence and ethics. Silent Spring thus stands as a foundational text of modern environmentalism, one that transformed private concern into public action and permanently altered how Americans understood their place within the natural world.

Bibliography

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

Lear, Linda. Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. Henry Holt, 1994.

Rome, Adam. The Genius of Earth Day. Hill and Wang, 2013.

Graham, Frank. Since Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin, 1970.

U.S. Congress. Pesticide Control Act Hearings, 1963.