The energy crisis of the 1970s was more than a period of economic hardship. It was a reckoning with the moral and structural limits of the American way of life that had long been in place. For decades, cheap and abundant energy had sustained American prosperity, suburban growth, and industrial dominance. When that system faltered, it revealed both an economic vulnerability and a crisis of national identity. The disruptions of the decade forced Americans to confront a sobering reality. That reality being that their postwar confidence in endless growth and consumption was unsustainable in a world of increasingly finite resources. No president faced this challenge more directly, and more painfully, than Jimmy Carter. His attempts to confront the crisis as both a practical and moral dilemma laid bare the tensions between America’s ideals of freedom and the discipline imposed by scarcity.

The Roots of Dependence

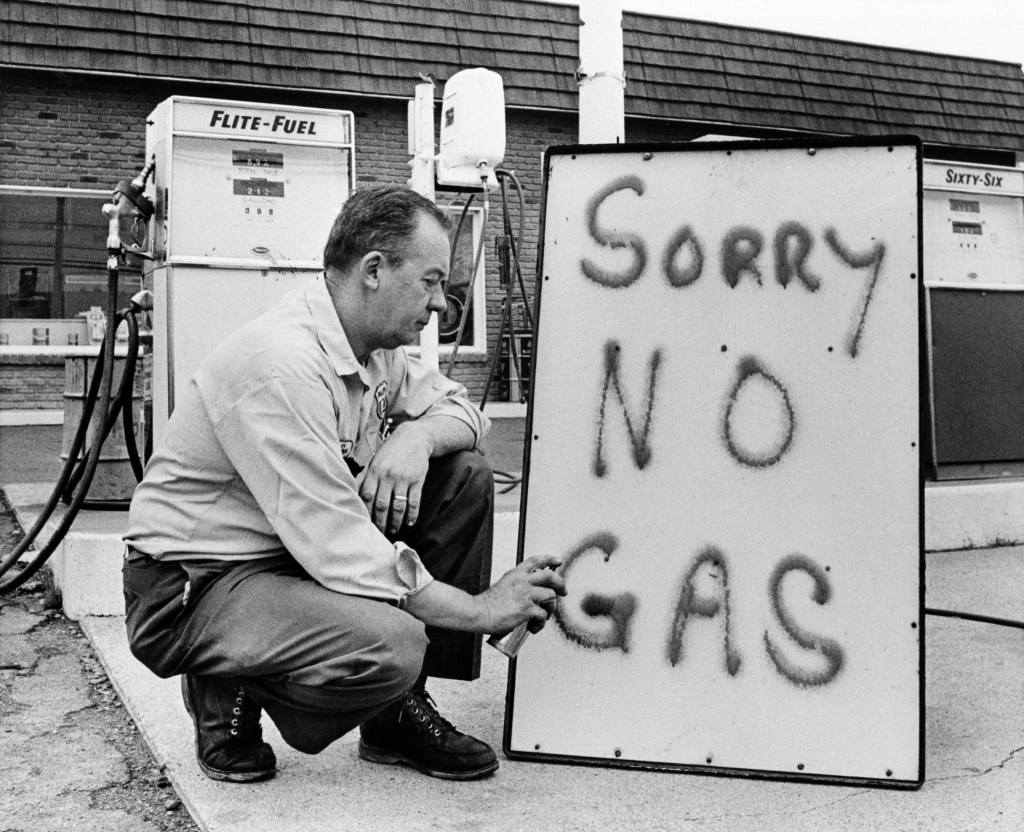

By the mid-1970s, the United States had become deeply dependent on imported oil, with much of it coming from politically unstable regions, namely the Middle East. The 1973 Arab oil embargo and subsequent price shocks exposed how vulnerable the nation’s economy was to global forces beyond its control. Gasoline shortages, long lines at service stations, and rising costs of living dispelled the illusion of postwar abundance. Yet the deeper crisis was psychological. Americans had grown accustomed to an economic model premised on consumption without consequence. Energy, like prosperity itself, had seemed infinite. This was an assumption long held by Americans that the 1970s decisively shattered.

Carter’s Moral Framing of the Crisis

When Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, he inherited both an energy problem as well as a public extremely weary of inflation, unemployment, and political disillusionment. Unlike his predecessors Nixon and Ford, Carter framed the energy crisis as more than a logistical issue of supply and demand. In his addresses to the nation, he described it as “the moral equivalent of war,” a test of whether Americans could unite in the face of shared sacrifice.¹ His proposed solutions included conservation, investment in renewable energy, and reduced dependence on foreign oil, and were rooted in both pragmatism and principle.

Carter’s rhetoric sharply departed from the optimism of earlier decades. He argued that the crisis demanded a redefinition of freedom. Carter argued it was not the right to consume endlessly, but the responsibility to sustain the collective good. In doing so, he challenged the prevailing ethos of abundance that had defined postwar America. This moral framing was intellectually honest, but politically perilous. Many Americans, exhausted by years of economic turmoil, did not want to hear that their habits and expectations were the problem.

The “Crisis of Confidence” and Public Backlash

Carter’s 1979 “Crisis of Confidence” speech epitomized this tension. Rather than offering reassurance, he told the nation that its troubles stemmed from a spiritual erosion, a loss of purpose, and shared values.³ The address was remarkable in its candor, diagnosing the energy crisis as a symptom of a deeper cultural malaise. Initially, the speech was well received. Millions of Americans praised Carter’s honesty and moral seriousness. However, goodwill quickly evaporated as shortages continued and inflation persisted. The president’s message, however accurate, came to symbolize defeatism.

The backlash revealed the limits of moral persuasion in a consumer democracy. Carter had asked Americans to confront the contradictions of their prosperity. He asked the citizens to accept economical restraint as a patriotic duty. Yet, the prevailing political mood of the late 1970s demanded optimism, not austerity. His call for sacrifice clashed with a society increasingly skeptical of government authority and nostalgia for a simpler narrative of national greatness that had been espoused by multiple American presidents preceding Carter. Historian Meg Jacobs noted that Carter’s realism about limits collided with a culture that still believed in boundless possibility.⁴

The Ideological Consequences

The energy crisis thus became a crucible for the broader ideological shift that defined the end of the 1970s. Carter’s appeals to discipline and conservation represented one vision of the American future, being pragmatic, interdependent, and environmentally conscious. The rise of Ronald Reagan’s conservatism represented another, which can be characterized as restorative, market-driven, and defiantly optimistic. Reagan dismissed Carter’s warnings about scarcity, declaring that “there are no such things as limits to growth, because there are no limits on the human capacity for intelligence, imagination, and wonder.”⁵ The public’s embrace of that message reflected the fatigue associated with the energy crisis, and more importantly, a reassertion of the nation’s self-image.

In this sense, the energy crisis did not simply reshape policy. It redefined the boundaries of political possibility. Carter’s defeat in 1980 symbolized the rejection of a politics of limits and the return to a politics of confidence. Yet his warnings about dependence, waste, and sustainability have echoed through subsequent decades of climate and energy debates. The crisis revealed an enduring contradiction in American life: the tension between material abundance and moral restraint, between optimism and realism.

The Unfinished Reckoning

The energy crisis of the 1970s was a mirror held up to the nation’s soul. It revealed the fragility of the economic order that had underwritten postwar prosperity and tested whether Americans could adapt to a world defined by interdependence and limitation. Jimmy Carter’s response, which was earnest, principled, and politically costly, reflected an attempt to confront that reality honestly. His failure was not merely personal or partisan but symptomatic of a society unwilling to accept that its greatest strength, being optimism, could also be its blind spot.

In the end, the energy crisis was less about oil than about identity. It forced the United States to ask whether its promise of freedom could survive in an age of scarcity. That question, unresolved in the 1970s, remains central even today.

- Carter, Jimmy. “Address to the Nation on Energy.” April 18, 1977.

- Schlesinger, James. Energy in the American Economy, 1850–1975. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981.

- Carter, Jimmy. “Address to the Nation on Energy and National Goals (‘Crisis of Confidence’).” July 15, 1979.

- Jacobs, Meg. Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and the Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s. Hill and Wang, 2016.

- Reagan, Ronald. “Remarks at Convocation Ceremonies at the University of South Carolina in Columbia.” September 1983.