The Cuban Missile Crisis was not only the most dangerous confrontation of the Cold War. It was the defining moment of John F. Kennedy’s presidency. The events of October 1962 tested the limits of U.S. power, as well as President Kennedy’s political and rhetorical authority at home. The administration’s deft navigation between military pressure and diplomatic compromise prevented a nuclear catastrophe, but it also transformed Kennedy’s overall standing among American citizens. In the aftermath, Kennedy emerged as simultaneously a Cold War steward and a leader who had demonstrated prudence, resolve, and restraint in his approach to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Ultimately, the crisis reshaped public confidence in the presidency itself, revealing how foreign-policy decision-making could fundamentally alter domestic perceptions of leadership.

Seeking Authority

When Kennedy entered office in 1961, his leadership was not universally admired. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 damaged his credibility and fueled perceptions that he was too young and inexperienced to manage global crises.¹ During the early period in office, many citizens viewed President Kennedy through a lens of cautious skepticism. They saw him as energetic and eloquent, yet untested. Cold War anxieties only amplified these concerns, as the Soviet Union appeared increasingly assertive in Berlin, the developing world, and the nuclear arms race. The administration’s own rhetoric about American credibility put Kennedy into a difficult position, as any future test of willpower would serve not just as a geopolitical trial but as a national referendum on his competence.

These vulnerabilities significantly influenced how Kennedy approached the Cuban Missile Crisis. The stakes were not solely strategic. For him, they were personal and political. President Kennedy understood that another foreign policy failure, so close to the Bay of Pigs Invasion, could destroy public confidence and undermine the very legitimacy of his presidency.

Crisis, Calculation, and Public Image

The discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba placed Kennedy in an impossible position. Publicly, the United States could not appear weak. Privately, Kennedy feared that a military strike could trigger uncontrollable escalation between the two global superpowers. The deliberations of the Executive Committee reveal a president acutely aware of the relationship between foreign actions and domestic legitimacy.² While many advisers pushed for an immediate airstrike, Kennedy resisted, arguing that such an attack would echo the very aggression the United States condemned in its adversaries.

His pragmatic decision to impose a naval quarantine reflected a deliberate attempt to preserve both strategic advantages and moral authority. In the case of the latter, President Kennedy’s decision allowed the administration to demonstrate firmness without locking the country into immediate war. To the public eye, the quarantine represented calm, rational leadership under extraordinary pressure.

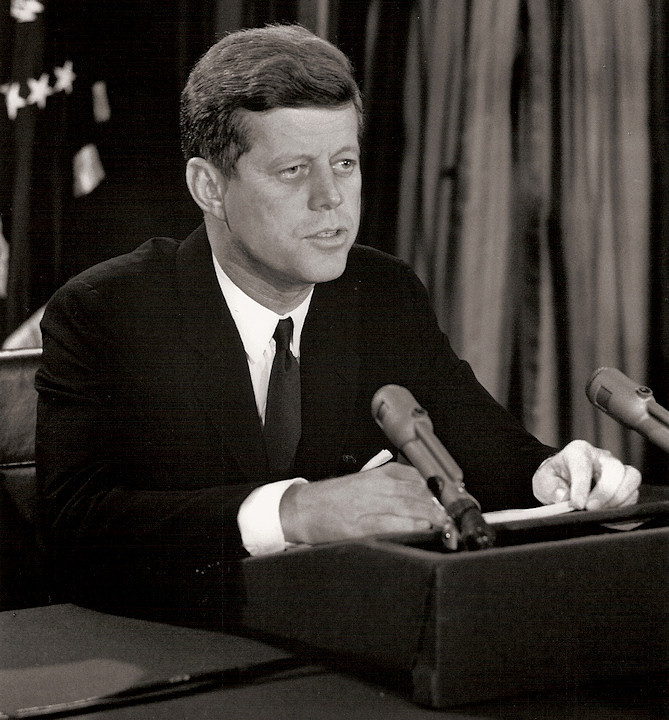

Kennedy’s televised address to the nation on October 22nd played a critical role in shaping public perception.³ In stark and steady language, he explained the threat and articulated his administration’s response as both decisive and measured. Millions of Americans who had previously questioned his strength now saw a president willing to confront danger without succumbing to panic. His approval ratings surged.

Compromise and the Politics of Victory

The crisis ended through a negotiated compromise. Soviet missiles were withdrawn from Cuba, and the United States privately agreed to remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey while pledging not to invade Cuba.⁴ That secrecy mattered. To the public, Kennedy appeared to have forced a unilateral Soviet retreat. He became a symbol of American resolve.

In truth, the outcome was more ambiguous. However, ambiguity served the political interests of President Kennedy. At a moment when Americans were terrified of nuclear war, what mattered was not the precise balance of concessions but the perception of presidential mastery. President Kennedy’s blend of firmness and restraint created the image of a leader who had guided the nation through its most dangerous Cold War moment without sacrificing principle or peace.

The Crisis and the Transformation of Public Trust

In the months that followed, Kennedy’s public image underwent a transformation. Contrasting sharply with the doubts that followed the Bay of Pigs, the missile crisis framed him as a sophisticated strategist capable of navigating complexities beyond public view. Surveys conducted in early 1963 showed a dramatic increase in Americans’ confidence in his judgment, particularly among groups previously skeptical of his leadership.⁵

The crisis also reshaped broader expectations of presidential authority. Citizens saw firsthand that modern leadership required not only military capability but deliberate reflection, consultation, and restraint. Kennedy’s private willingness to compromise, paired with his public projection of steadiness, became a template, one that later presidents struggled to emulate.

Legacy and Memory

President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 froze public memory at the moment when his reputation was at its height. The Cuban Missile Crisis became central to this legacy. For many Americans, it symbolized the ideal of presidential leadership: calm, balanced, and morally anchored. Scholars have since debated the accuracy of this perception, noting that political calculation and secrecy significantly influenced the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Yet, these complexities did little to diminish the enduring effect the episode had on President Kennedy’s standing following his assassination.

The Cuban Missile Crisis ultimately demonstrated that public perceptions of leadership are forged as much in moments of danger as in moments of achievement. President Kennedy’s handling of the crisis did not solve the dilemmas of the Cold War, but it redefined his presidency by illustrating that strength could coexist with restraint. In an era marked by ideological rivalry and nuclear fear, Kennedy’s actions provided Americans with a rare sense of confidence, anchoring his place in American political memory.

Bibliography

Beschloss, Michael. The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khrushchev, 1960–1963. 1991.

Dobbs, Michael. One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War. Knopf, 2008.

Gaddis, John Lewis. Strategies of Containment. Oxford University Press, 1982.

Kennedy, Robert F. Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. W. W. Norton, 1969.

Stern, Sheldon M. The Week the World Stood Still: Inside the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis. Stanford University Press, 2005.