By Deon Nguyen

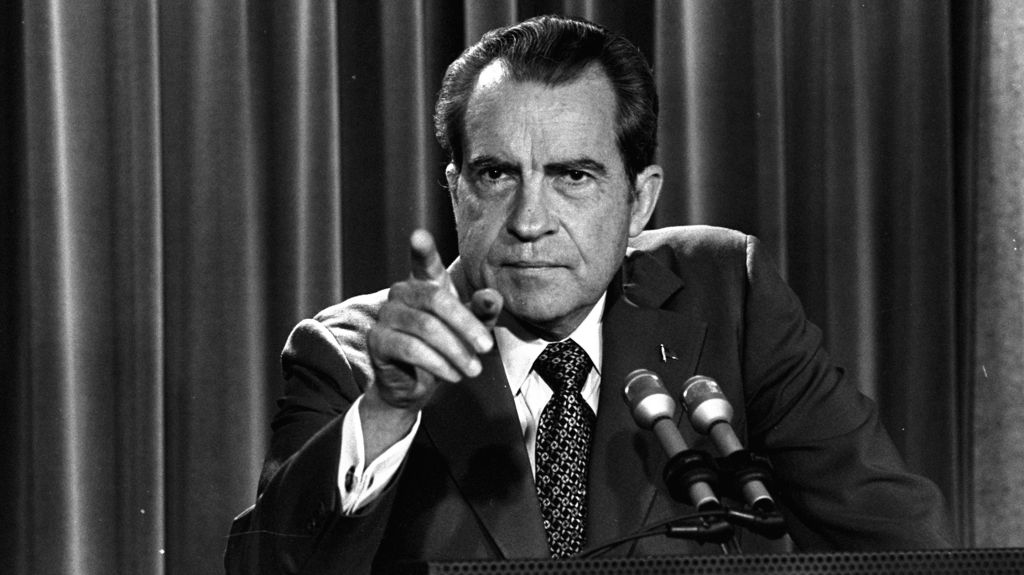

The Watergate scandal represents a pivotal moment in American political history. More than the exposure of presidential misconduct, it marked a profound rupture in public confidence. Richard Nixon’s central role in the events surrounding Watergate deeply undermined the legitimacy of federal institutions. In the aftermath, the average American citizen viewed the federal government not as a guardian of democratic values, but as a site of deception and abuse of power.

Prior to Watergate, many Americans held a largely deferential view of the presidency. Despite the social upheaval of the 1960s, the executive office remained a symbol of national stability. Presidents were seen as public servants, fundamentally aligned with the public good. Their authority, even when questioned, was largely respected. Watergate, however, brought to light the extent to which that image could be deliberately manipulated.¹ It exposed the machinery of political power in previously unthinkable ways for the average citizen. The scandal shattered illusions about executive virtue and permanently altered how Americans relate to their leaders.

The revelation that operatives connected to Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (so-called CREEP) had orchestrated the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters ignited suspicion. Initially dismissed by some as a minor incident, the event quickly escalated in gravity as investigative journalists, most notably Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post, began to uncover a pattern of deceit and obstruction. As congressional committees launched formal investigations, more disturbing facts emerged: hush money payments, misuse of government agencies like the FBI and CIA, and attempts to interfere with legal proceedings.²

The Nixon administration’s persistent denials, later proven false, were perceived as intentional efforts to deceive the American people. This perceived betrayal triggered a marked deterioration in civic faith. Citizens who had previously trusted the president as a man of his word found themselves watching in disbelief as lie after lie unraveled. Public trust, once rooted in patriotic loyalty, was now consumed by skepticism and doubt. The feeling of betrayal was especially potent because it came from the highest office in the land, and its implications went far beyond Nixon as an individual.

The Presidency and the Crisis of Credibility

A central turning point in public perception occurred with the release of the White House tapes. These secret recordings, made by Nixon himself, provided irrefutable evidence of his complicity in the cover-up. The so-called “smoking gun” tape, released in August 1974, demonstrated that he had sought to impede the FBI’s investigation into the break-in.³ For many Americans, this was an unambiguous confirmation of executive dishonesty and abuse of power.

The impact on public opinion was immediate and severe. Surveys conducted in 1974 documented a sharp decline in confidence in the presidency and Congress.⁴ According to data from the Pew Research Center, trust in government plummeted from 68% in 1968 to 36% by the end of 1974. The televised Senate hearings further exposed the inner workings of a corrupt administration.⁴ Millions of Americans tuned in daily, watching as former White House staffers detailed illegal activities and systemic corruption. Citizens who watched these proceedings began questioning not only Nixon but also the broader system that enabled such misconduct.

The scandal’s effect was magnified by its visibility. Unlike past political controversies, Watergate unfolded in the national spotlight. Media coverage was relentless, and Americans witnessed government officials admit to deception under oath. This transparency paradoxically deepened distrust. Rather than restore faith in the system by showcasing accountability, it revealed the full extent of institutional vulnerability.⁵ The public began to ask hard questions: If Nixon could get away with this for so long, what else had been hidden? What other lies had gone unchallenged?

Long-Term Consequences for Civic Engagement

The psychological impact of Watergate extended far beyond Nixon’s resignation. It contributed to the emergence of a more cynical and disengaged electorate. Voter turnout in the years following the scandal declined, and political apathy began to rise. No longer was political participation seen as a route to national progress. For many citizens, it represented a futile engagement with a corrupt system.⁶ Political campaigns increasingly emphasized image management and damage control, further alienating voters from substantive discourse.

The scandal also catalyzed a transformation in journalistic norms. Reporters increasingly assumed an adversarial posture toward public officials. The era of “access journalism” gave way to investigative journalism, driven by a duty to expose wrongdoing. While this empowered the press to hold leaders accountable, it also fostered a climate of suspicion.⁷ Citizens learned to view political narratives with skepticism, often defaulting to disbelief. This wariness, while a safeguard against blind loyalty, also made it harder to build consensus or sustain optimism about the government’s ability to function effectively.

Legislative reforms in the wake of Watergate sought to restore public confidence. The Federal Election Campaign Act Amendments of 1974 introduced new transparency requirements, limited campaign contributions, and established the Federal Election Commission.⁸ These efforts aimed to curtail the influence of money in politics and prevent future abuses. While they marked a significant step toward accountability, they did not substantially reverse the erosion of trust. The symbolic weight of Nixon’s misconduct continued to cast a long shadow over American politics, mainly as new scandals emerged in subsequent decades.

The Enduring Legacy of Disillusionment

In the final analysis, Nixon’s role in the Watergate scandal irrevocably altered the public’s relationship with government. The executive branch, once imbued with a sense of patriotic reverence, became a source of apprehension and skepticism. This shift marked the beginning of a more adversarial civic ethos in the United States. The presidency was no longer viewed as a moral authority but a politically self-interested institution.⁹ The myth of presidential infallibility was shattered, replaced by a more complex, and often darker, understanding of political power.

Even decades later, Watergate remains a cultural touchstone for political corruption. The suffix “-gate” has been applied to numerous subsequent scandals, like “Irangate”, reflecting its lasting linguistic and psychological impact. It is a shorthand for government betrayal and serves as a benchmark against which all other scandals are measured. The scandal fundamentally reoriented public expectations of federal transparency and accountability. For the average American citizen, trust in government has never fully recovered from Nixon’s betrayal.

In conclusion, Watergate taught the nation an indelible lesson: democratic institutions are only as trustworthy as the individuals who run them. While mechanisms of accountability remain in place, the events of the early 1970s continue to echo through American political life. They serve as a sobering reminder that power must always be checked, and that public trust, once lost, is exceedingly difficult to regain.

Bibliography

1. Schudson, Michael. Watergate in American Memory: How We Remember, Forget, and Reconstruct the Past. Basic Books, 1992.

2. U.S. Senate Watergate Committee Hearings, 1973. Congressional Record.

3. United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974).

4. Pew Research Center. “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2023.”

5. Woodward, Bob, and Carl Bernstein. All the President’s Men. Simon & Schuster, 1974.

6. Broder, David S. “Watergate’s Impact on Public Opinion.” The Washington Post, August 9, 1974.

7. Kalb, Marvin, and Stephen Hess. The Media and the War on Terrorism. Brookings Institution Press, 2003.

8. Kutler, Stanley I. The Wars of Watergate. Knopf, 1990.

9. Ambrose, Stephen E. Nixon: Ruin and Recovery, 1973–1990. Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Leave a comment